911 & Porsche World columns by Karl Ludvigsen

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Return to Karl Ludvigsen main page

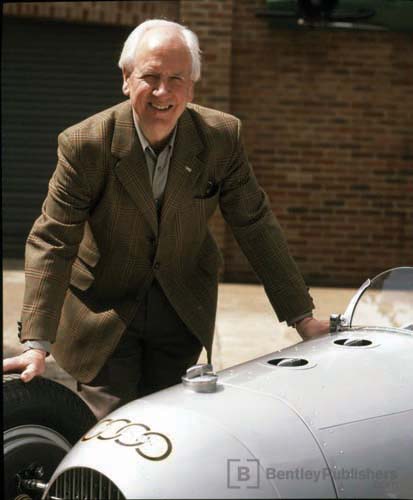

Ferry Stories

In his valedictory column Karl Ludvigsen reflects on Ferry Porsche the man, as revealed in frank conversations. His spirit of canny conservatism in the service of great sports cars long animated Porsche the auto maker.

I first met Ferry Porsche when he and Huschke von Hanstein came to New York in 1957. Ferry was in the USA to accept a Franklin Institute award that recognised the role of his father in the creation of the VW Beetle. Porsche organised a reception for Ferry and Huschke in New York to which I, a humble technical editor of Sports Cars Illustrated, was asked along. Huschke gave me my first Porsche lapel pin, which I managed to hang on to for many years.

I reflected on this first meeting after a stint in 1996 as an honorary judge at the 50th-anniversary Porsche Parade at Hershey, Pennsylvania. On the same panel was actor and comedian Jerry Seinfeld. My colleagues at Bentley Publishing arranged for me to have some one-on-one time with Jerry, who is an enthusiastic owner, driver and admirer of Porsches. During our chat he said to me, in his no-nonsense way, 'You knew Ferry Porsche, didn't you? What was he like?'

Yes, I did know Ferry Porsche. He was of medium height with light-brown hair and a clear gaze. He spoke in a gentle tenor with a lilt that betrayed his Austrian origins. He preserved as well an Austrian awareness of the ridiculous, an appreciation that although things had at times been bad, they could always have been a lot worse. It was fascinating to discuss Porsche affairs with a man who had driven the Auto Unions and shaken hands with Hitler.

Disappointments loomed large in the Ferry story. During the years when he worked for his demanding father he suffered from the same abruptness, the same unwillingness to praise, as his colleagues. If it was meant as a way of hardening the young engineer, it failed. Ferry remained a man who got results by knowledgeable persuasion, not by fiat. He brought all of his unequalled experience and close observation to every decision, an attribute that could be frustrating to his colleagues but yielded great results in the long run.

Perhaps Ferry's deepest disappointment was his father's decision on the distribution of the Porsche patrimony at his death in 1951. The semi-feudal central-European custom was that the eldest son received the main inheritance, the house and the business, while token gifts were made to others. Ferry Porsche had every reason to expect that he'd be similarly blessed. Instead, to his astonishment and dismay, Ferdinand Porsche divided ownership of his holdings equally between Ferry and his sister Louise without, said grandson Ferdinand Piëch, 'giving the slightest inkling as to whom he'd prefer to entrust the leading role in the clan.

'Apart from the fact that the daughter was five years older,' Piëch continued, 'she always seemed rather more mature, grown-up, stronger than her brother. At least in my view she'd never lost a certain advantage, and there's much evidence that my grandfather saw it the same way.' 'My father absolutely wanted to bring my sister into the company's management,' Ferry acknowledged. 'It would have been more correct if my father had gone the way of the Rothschilds and said: "One bears the responsibility, one does it."'

Brother and sister found a Solomonic solution. They took joint ownership in their respective enterprises, which however remained separate in their management. Ferry ran the car and engineering company in Stuttgart while in Salzburg Louise headed the Austrian import company for VW and Porsche. 'Each sibling was ready to help the other,' said eldest grandson Ernst Piëch, 'but they remained separate.'

Little changed over the years in the high-tension relationship between brother and sister. Yet when Ferry was released from detention in 1946 it was to his sister that he turned, for long walks in the countryside to share his pent-up emotions, rather than to his wife. 'One could sense that the relationship between the siblings Louise and Ferry was exceptional,' said Ferdinand Piëch. 'They loved and hated each other in the intense, violent manner that's customary between brother and sister. And naturally it fitted that picture that in high old age, in spite of all that separated them, they were again and again together.'

Forthright to a fault, Ferdinand Porsche had been constitutionally incapable of appreciating the attributes that Ferry brought to business management. He was conservative, to be sure. That very conservatism contributed to the remarkably subtle and at times glacial evolution of Porsche's cars from the 356 through the 911 to 1972, when Ferry and his relations stepped back from the company's management. Without mentioning the 924 and 928, Ferry said later that he wished he'd stayed longer at the company's controls.

On 15 October 1973, when Ferry's departure from direct management was still fresh, I sat with him in his office in a villa on Stuttgart's Robert Bosch Strasse to discuss the company and its evolution. This was the first time that I or anyone else had heard of the 1.5-litre sports car that was designed before the war with the aim of creating the first Porsche-branded production model. 'It had a five-cylinder engine,' he told me. 'It's a very smooth, well-balanced engine,' he said, 'with nice firing intervals.' Only when I went to the files to check on this hitherto-unknown design did I discover that Ferry had recalled the concept but not the actuality: in fact the Type 114 'F-Wagen' had a V-10 engine.

Ferry described to me the way he had moved a small engineering detachment from Gmünd back to Stuttgart late in 1949. They set up shop at the Porsche villa on the Feuerbacherweg, using the garage as a workshop-as it had been when the first VW prototypes were built-and the room usually occupied by the family cook, which they called their 'three-metre office'.

It wasn't a given that Porsche would make cars in Germany, Ferry explained: 'In 1951 there were many discussions in the family about whether we should continue what we started in Gmünd with the 356. I was always for it, and after I pressed ahead there were no more arguments. In fact there were, though-arguments about which part pays for what. If we pay for 50 per cent of engineering work on cars with cars, for example, who is to say how the other 50 per cent was earned with consulting? You can divide up the amounts any way you want.'

When Porsche started making cars in Germany it rented space from coachbuilder Reutter, because the US Army still needed their nearby Werk I as a motor pool. 'That was our greatest good fortune,' Ferry told me with a knowing smile. 'Other firms had buildings, tools and so forth, but they didn't know what to do, which cars to make. They had overheads but no cash flow. We started with cash flow but with no overheads!' With their earnings and royalties from Volkswagen they soon built up a war chest.

'We then saw that production needed to increase,' Ferry continued, 'so we built Werk II. It was ready in 1956. Then that same year, exactly on the 25th anniversary of our company, the Americans gave back our Werk I. If we'd known that would happen we might never have needed Werk II!' This was typical Ferry, bemused by such coincidences and second-guessing past decisions. Of course both workshops were soon needed to meet demand.

Ferry Porsche explained to me the background of the relationship with Reutter. 'Father Reutter was killed by bombing here in Stuttgart,' he said, 'and his son was killed in the war. There were eight heirs but none of them had any knowledge of the business so they hired a manager. When they had to invest more, as our production increased, the heirs didn't want to, so the manager advised them to sell the body plant. In a very difficult decision, we at Porsche bought it in 1963. It was very hard to get the necessary capital together. We had to make an investment which brought in nothing new. We laid millions on the table and nothing changed.'

While sports-car production boomed, Porsche's contract with Volkswagen gave little satisfaction apart from royalties. 'After the war,' said Ferry, 'our first work for Volkswagen was to design a new car, keeping the existing engine. It had a completely integral structure and MacPherson-strut front suspension. But then the Beetle was selling so well they decided not to build it.' Many more prototypes for Wolfsburg met the same fate. 'That's why I always thought that we should keep building cars,' Ferry told me. 'At least in one area we can show that we are always up to date, even if the others for whom we work don't produce what we have designed. If we weren't building cars, nobody would speak about us any more.

'Others are making sports cars,' Ferry Porsche explained, 'but no one makes a car like we do, made specially for the purpose, down to every last screw and bolt. Others in Italy do it, but their cars cost twice as much as ours.' As a summary of what makes Porsche Porsche, that's still pretty good today.

- Karl Ludvigsen

The Unasked Question

Its membership in the VW Group has brought Porsche both new opportunities and new challenges, especially in engineering, in which it has a proud tradition. Karl Ludvigsen looks for answers to a question no one has asked.

Since the arrival of Matthias Müller as Porsche's new chief he's been quizzed from all quarters about the outlook for the company's products and the nature of Porsche's relationship with the rest of the sprawling VW Group. He's been pretty forthcoming.

A crucial question, of course, is the nature of Porsche's future role in respect of the Group's sports cars. Audi has been challenging Porsche in this sector with its TT and R8 derivatives, the latter especially a no-excuses sports car. Nor is Lamborghini to be overlooked, in its role as an associate of Audi, or Bugatti, which is linked with Bentley in the Group hierarchy.

Müller described an early-2011 conclave of senior VW bosses at which the question was aired: 'What is the most sporty brand in the Group? And we decided that that is always Porsche. Due to that fact, we said that the modular systems of high-performance sports cars have to be the responsibility of Porsche.'

This was a signal victory for the Zuffenhausen outfit. It puts Porsche in charge of platforms for all front-mid-engined and rear-mid-engined sports cars, those of Audi and Lamborghini as well as Porsche. The assignment successfully fended off a proposal from Wolfsburg that future 911-class cars be based on VW underpinnings. This was clearly a step too far; Porsche will control development of all its boxer-engined sports cars.

Matthias Müller is open, however, to the use of VW components for a sub-Boxster entry that he fondly calls the '550'. It would be derived from the Boxster, he said, 'which we can make a little bit cheaper using some parts of the modular system of Volkswagen, specifically the MQB-the next Golf platform. So that could be a way to have a platform for a smaller sports car.' In Wolfsburg jargon this is the Modularer QuerBaukasten or matrix for transverse-engined cars-perhaps a hint that the '550' could have an east-west mid-mounted engine.

Impressively, as well, Porsche was awarded responsibility for the MSB or Modularer StandardBaukasten, which will be used for the Group's sporty sedans with rear- and four-wheel drive. 'The basis is actually the Panamera platform,' Müller explained, 'which we will develop in the next generation. Concept-wise it is the platform which fits the best for huge cars.' By 'huge' he meant not only the Panamera itself but also the Bentley Continental or the mooted four-door Lamborghini based on the Estoque concept car shown in Paris in 2008.

Müller didn't rule out use of the MSB underpinnings for a future Audi, such as the A8, but stressed that it such a decision was up to Audi. The Ingolstadt sister in the VW Group has its own MLB platform for products with longitudinal engines as the acronym suggests. This has already been earmarked for the third generation of the Q7, Cayenne and Touareg.

Nor is this all on the groaning platter of the Weissach engineers. 'There are two other Group-wide fields that we take care of,' Matthias Müller added: 'light-weight construction and engine expertise.' The assignment to mastermind lightness for the VW Group arose during a discussion with Ferdinand Piëch, said Müller. 'We quickly came to the theme of weight reduction-and thus efficiency-and that here Porsche must again assume the technological leadership. We want to deliver an argument to our customers that says it's not immoral to drive a sports car.'

As for 'engine expertise', this is a topic of immense importance to a Group that has always prided itself on the outstanding power-unit skills in Ingolstadt and Wolfsburg that have given birth to such notable engines as the pioneering VW Diesels and the W-format units that are unique in the industry. It won't be easy for Porsche to prevail across the group in this specialisation. This will be one of the tasks of its new engineering board member, Wolfgang Hatz. From Porsche by way of VW, Hatz has the asset of engine expertise.

Soon after taking over at Porsche in October of last year Matthias Müller expressed one of the goals of his administration. 'It would be fatal,' he said, 'if we weren't to enhance the profits of other brands in the Group effectively by using Weissach, the company's third large development centre. I'm confident that we'll have a substantial role.' He has achieved this aim with stunning success.

The VW Group signals its confidence in Porsche with the investment that it is planning over the coming five years. A billion euros are earmarked for enhancement of facilities for production, product planning and engineering. As well staffing is expected to rise by eight per cent or some 1,000 personnel, half of whom are needed in engineering to carry out the major new assignments described above-not to mention continuity of the traditional core Porsche products.

The foregoing begs a crucial question: what is to be the fate of Porsche's vaunted engineering services to outside clients? Opening in the Porsche Museum on 21 June is a special three-month exhibition on the subject of 'Porsche Engineering - 80 Years of Porsche Designs'. It takes its timing from 15 April 1931, the date on which Ferdinand Porsche and his backer Adolf Rosenberg officially registered their new business, an engineering consultancy that aimed to provide design services to clients.

In 2006, when the dedicated Porsche Engineering Group (PEG) and its 500-strong staff celebrated their 75th anniversary, they produced a book that told the early story of Ferdinand Porsche's creativity and highlighted the major projects carried out for customers after the 1931 founding of the Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche GmbH.

Unforgettably the 1930s brought the high-profile engineering of the Grand Prix Auto Union and the Volkswagen, projects that reminded the world of Porsche's expertise. The 1950s saw new prototypes for VW and the design of an all-new car for Studebaker. The 1960s brought the engineering of the Leopard armoured assault vehicle while the 1970s launched major work on the Russian Lada Samara and the 1980s witnessed the design of engines for Seat, Harley-Davidson and TAG, the turbo V-6 that won championships in McLarens.

Off the beaten track of vehicle design were such projects as forklift trucks for Linde and a flight deck for Airbus. These were godsends during periods like the 1980s when the designs of Porsche's own products were quasi-static, leaving stylists and engineers with lots of time on their hands. At various times efforts were made to expand the PEG's activity, which was always seen by the senior members of the Porsche and Piëch families as the vital core of Porsche's competence. A Detroit office, for example, was opened and later closed.

Since October of 2009 the PEG's board chairman has been Malte Radmann, who is also handling its commercial arrangements. The Group's technical director is Dirk Lappe, who came up through electronics. Today, says Porsche in its 80th-anniversary celebration. 'Porsche Engineering carries out development work on behalf of car manufacturers and suppliers as well as companies from other sectors, combining the skills of Porsche as a series manufacturer, technology company and engineering service provider and making these available to third parties.'

But does it? This is the unasked question. Porsche refuses to release information on the number of the PEG's third-party customers or the share of turnover for which it is responsible. It was the recent PEG custom to publish a magazine at the beginning of each year to tout its competence and the capabilities available at Weissach. So far in 2011, well into the year, no new magazine has been published. Nor for many months has any announcement been made of a new contract for the PEG.

Porsche may be experiencing a major collision between its hallowed tradition of design for customers and the tremendous demands being made on its engineering capabilities by the tasks that it has accepted-indeed lobbied for-within the VW Group. The PEG's 500 staff would easily be swallowed up by these commitments, to meet which 500 more engineers are being recruited.

Another straw in the wind gives a hint. During 2010 the VW Group bought 90-per cent ownership of Italdesign, the company founded in 1968 by Giorgetto Giugiaro and Aldo Mantovani. Folded into the VW empire, Italdesign will no longer work for third parties. Its current clients, said Giugiaro, could either withdraw from their commitments or have them completed. After that no new outside projects will be accepted.

Is the same thing happening at Porsche? Unasked, the question is unanswered. It was once the ambition of VW's Heinz Nordhoff to gain complete and exclusive control of Porsche's engineering expertise. Dedicated as he was to Porsche's hard-won independence, Ferry Porsche saw through Nordhoff's scheme and thwarted it. Now in the 21st century a descendant of the founder, VW's Ferdinand Piëch, may have achieved what Nordhoff could not. It would be his definitive rude gesture to the company that showed him the door almost 40 years ago.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Porschefying History - Part 4

In one of the most impressive and complex automotive recreations, Porsche funded the revival of Ferdinand Porsche's hybrid of 1900. Then it corrupted the achievement by making needlessly exaggerated claims for its Semper Vivus.

Backed by the Vienna firm of Jakob Lohner, coachbuilders to the crowned heads of Europe, Ferdinand Porsche built his first racing car in 1900. Like all his earliest cars it was battery-powered and propelled by electric motors built into the front wheels. On both sides of its nosepiece were triangles from which three running legs protruded, a well-known motif in both Sicily and the Isle of Man. It symbolised the patented System Lohner-Porsche.

The racing Model J Lohner-Porsche had a tubular steel frame and suspension for its front wheels only. The driver crouched over a raked steering column behind a wedge-shaped prow. A second seat was at the rear. Below them a coil-sprung box carried the battery pack, containing 74 cells with a 148-volt potential, Porsche's biggest and heaviest yet. It contributed most of the bulk of the stripped-down 2,490-pound Type J.

This racy Lohner-Porsche was built expressly to compete in the prestigious and demanding Semmering Hill Climb near Vienna, driven by the designer himself. On race day, 9 September 1900, his time at the half-way mark promised victory but his drive tyres failed him. Porsche's style was fast but rough; on the big day he pressed too hard. He struggled forward on the naked rims but they scrabbled ineffectually on the loose surface. His racer slewed to a standstill.

Failing so openly mortified Porsche, who stood stranded at the roadside. When a passing official asked after his welfare, the distressed designer answered, 'I'd really have preferred that both the car and I fell off the cliff!' It was a setback in image and prestige for Lohner, which had entered a second Lohner-Porsche for Johann Maschl that failed to figure among the finishers.

Porsche assured his chief Ludwig Lohner that a result could be obtained, so arrangements were made to with the Austrian Auto Club to have official timing for a private attack on the hill two weeks later. The Semmering was wreathed in mist for an early-morning start. Observers heard the hooting of Porsche's wheel-mounted horn before they saw him roll speedily and silently out of the mist. His clocking at an average speed of 24.88 mph was quicker than that of all participants a fortnight earlier save a solitary three-wheeled de Dion. Honour was satisfied.

Soon after this sprinting success Ferdinand Porsche completed another project based on a similar tubular chassis. It was the realisation of an idea that he'd had earlier in the year. In Vienna's AAZ of 25 February 1900 readers learned that Porsche and Lohner wanted 'to supply the vehicle with a portable charging station, which would enable it to generate so much fresh current during the journey that it could cover 95 miles.' This required no small amount of electrical engineering, at which Porsche was expert.

Like the racing car the new machine had a single driver's seat in front, behind a curved dust shield. Another seat at the extreme rear could accommodate two. Its battery box was like that of the racer but with 30 instead of 44 cells. The reduction was allowable because the new car carried its own charging station. Behind the front seats were two 3½-horsepower single-cylinder de Dion engines from Lohner's extensive inventory of past experiments. Both drove generators that delivered electricity according to Porsche's sophisticated system.

Each de Dion engine operated completely independently in all its equipment and interconnections to the batteries and motors, delivering a current of 20 amperes at 90 volts. Under way the generators' output was fed directly to the front-wheel motors unless it wasn't required, in which case it was diverted to the batteries. The latter then were switched into the circuit to augment the output of the generators when needed, for example on upgrades. In other words, it was a parallel hybrid as we understand the term today.

An appealing feature of Porsche's layout was that the generators were operated in reverse as motors, powered by the batteries, to start the de Dion engines. Each engine drove a pump that delivered its cooling water to an individual gilled-tube radiator alongside the prow.

The on-board charging station weighed 595 pounds. Also added were 220 pounds worth of full fuel and water tanks. Thanks to the reduction in battery weight, at 2,650 pounds Porsche's self-charging vehicle scaled little more than the same machine in all-electric racing form. Its name Semper Vivus reflected its 'always alive' capability.

With its lack of rear suspension and exposed booster engines, shielded only by side screens, this was a mere breadboard layout of the kind of vehicle Ferdinand Porsche had in mind. By the time Semper Vivus was displayed at the 1901 Paris Salon, together with a Lohner-Porsche electric car and fire truck, Porsche's thoughts had already raced ahead to new families of motor-wheels and new ways of powering them. The test car's success in providing a link between a gasoline engine and electric road wheels opened new horizons for both Porsche and Lohner. The idea's first manifestation was all but forgotten by its creator.

With the dawn of the hybrid era in the 21st century, Semper Vivus wasn't forgotten by the Porsche company. On 16 November 2007 it commissioned Hubert Drescher to build a replica of the long-lost pioneer. At his workshop in Titisee-Neustadt, near Freiburg in the depths of the Black Forest, Drescher began piecing together the information he needed to recreate this historic prototype in all its revolutionary complexity. He needed a lot.

The de Dion engines shouldn't be a problem, Drescher thought, only to find them thin on the ground. He was about to start making replicas when he found one in a Strasbourg flea market. The Porsche Museum's Klaus Bischof discovered another-with some useful spare parts-in Britain during a trip to Goodwood's Festival of Speed.

Helped by engineer Wolfgang Ertl, Hubert Drescher rethought the Semper Vivus electrical system. Original Porsche wheel motors were examined in museums in Budapest and Vienna to permit Ferdinand's brain waves to spark again. The inventor's patents gave clues to motor windings and the rotary control under the driver's seat that gave the vehicle three forward speeds, a braking mode, neutral and reverse, all managed by a single lever.

The sprung wooden battery case carried more modern cells, 44 in all of a fork-lift-truck pattern giving 88 volts. Drescher created gauges for voltage and current flow in turn-of-the-century style, saying that 'it shouldn't be possible to see that it's a reconstruction.' In all he and Erlt spent some 2,000 hours making this new Lohner-Porsche look old, an effort thought to have cost £570,000.

Early in 2011 the reborn Semper Vivus strutted its stuff on Porsche's Weissach skid pad. Its first public appearance was on the Porsche stand at Geneva in March-a fitting complement to the launch of the Panamera's hybrid version. In its press releases and an accompanying book Porsche hailed the Semper Vivus - alive again - as 'the world's first operational full hybrid automobile'.

This was another example of Porsche's predilection for rewriting history. The Stuttgart company finds it insufficient to celebrate the achievements of its founder without claiming priority for him. Porsche has to have done it first. This is regrettable because it debases the company's communications. Of course because Porsche says it, many editors think it must be true. It isn't.

Based on earlier tramcar designs, Chicago's W. H. Patton built vehicles in 1898-99 that drove their wheels by an electric motor powered by batteries that were charged by an on-board gasoline engine and generator. In 1896 both L. Epstein and H. J. Dowsing patented various combinations of these elements. In America gasoline-electric vehicles were produced by both Indiana's Munson and Illinois's Fisher at the turn of the century. A sophisticated mixed-system vehicle was exhibited in Paris in 1899 by Pieper of Liège, Belgium, an authentic pioneer of advanced electric cars. Porsche wasn't far behind, but he was by no means first.

As for Ferdinand Porsche, he and Ludwig Lohner abandoned their pioneering hybrid. The Semper Vivus disappeared from history while they concentrated on what the market wanted in the form of pure electric cars, on the one hand, and their electric-drive petrol-powered Mixtes, on the other. Though today's Porsche has often characterised the latter as hybrids, the Mixtes were in fact petrol-engined cars with electric transmissions. They had no battery motive power.

Even in far-away America due note was taken of what Porsche was achieving. There respected technical author Peter Heldt advised his readers, in July of 1900, that 'We know that a great Vienna firm is working on a vehicle of a concept of mixed systems.' For Ferdinand Porsche such recognition was sufficient. He found it satisfying to pioneer and patent successful new technologies. Unlike his boastful successors, he found the accomplishment its own reward.

- Karl Ludvigsen

The Private Life of 356-001

Iconic though it is in the history of the Porsche production car, the original 356 roadster was dispensed with surprisingly quickly after it had served its purpose. We track its remarkable post-Porsche history.

Though planned in principle in mid-1947-chief Porsche designer Karl Rabe was working on a one-fifth-scale drawing at Gmünd on 24 July-the first Type 356 roadster was only progressed as and when the necessary skills were available. In July of that year and again in November meetings took place with the British occupation officials in Klagenfurt who would have to bless Porsche's creation of an automobile, lest it be thought a new secret weapon. Inspection of its completed tubular space frame took place on 18 January 1948.

After the frame was ready, final assembly proceeded quickly. On the 5th of February the bare chassis was ready for the road. Naturally Ferry, one of the most experienced evaluators of automobiles in Europe, was first to try it out. On several of his outings with the bodyless car Ferry was accompanied by Robert Eberan von Eberhorst, then still a consultant on the Cisitalia Grand Prix project. At first silent, shaking his head, Eberan then said, admiringly, 'That's really something. And all that from Volkswagen parts!'

Next an aluminium body was needed. Erwin Komenda drew it, thereby establishing the basic look of the 356 coupes and cabriolets to come. The body was hammered out by star craftsman Friedrich Weber. Though Ferry Porsche later wrote that Weber needed 'a bit over two months to build that first body-not exactly a record time for a skilled artisan,' the actual timing indicates that he built it in a day or two more than three weeks.

Soon after the roadster's completion, on the 28th of April, Ferry invited his father to join him for a run south toward Spittal during which the 356 suffered a frame breakage. After repairs, works manager Otto Husslein took it for a shakedown run on the first of May. That he had something to learn about sports-car driving was shown by the dents in its tail that had to be repaired after his return.

On the 13th of May the roadster was undercoated in yellow, weighed and turned over to Ferry for further evaluation. A week later it was commandeered by Ferdinand Porsche and chauffeur Goldinger for an afternoon drive in the first car that was destined to carry the family name.

Finish-coated in silver-grey, the 356 was presented to the authorities in Spittal on 8 June for road registration. They recorded Porsche as the producer and the model as 'Sport 356/1'. Serial number was 356-001 and engine number was 356-2-034969. A picture appended to the application is the only known image of the roadster with its crude canvas top erect. Individual type approval was granted on 15 June with the awarding of registration number K 45 286.

Now branded as a 'Porsche', no longer thought of as a possible sports Volkswagen, the 356 roadster was driven to Switzerland late in June so it could be tested by journalists who were on hand for the Swiss Grand Prix on July 4th. Then it was driven back to Austria, where it was demonstrated before an appreciative crowd on 11 July 1948 at Innsbruck between races of the Rund um den Hofgarten meeting.

Thereafter the 356 roadster came to rest back in Switzerland, where the first orders for Porsche production cars originated. Its first owner after Porsche was the Riesbach Garage in Zürich. The garage's owner Josh Heintz bought the Porsche for 7,000 Swiss francs-about $1,750-in September of 1948; an Austrian export license was forthcoming on September 7th.

The Riesbach Garage put the Number One Porsche in its new-car showroom. Though the 356 was admired by many onlookers, no one had the courage to buy this unknown vehicle. A friend of the garage owner, Peter Kaiser, was willing to take the car for 7,500 francs-more or less as a favour to Heintz. Kaiser was told that a group of Swiss industrialists had wanted to manufacture it. He was sold the 356 on the understanding that they could buy the roadster back if they decided to proceed.

Not until 20 December was the car officially registered for the road in Switzerland, where it bore the plate number ZH20 460. The PORSCHE lettering on its front deck didn't meet with Kaiser's enthusiasm. He felt that it didn't fit well with other sports cars, which had sonorous, zippy names like Alfa Romeo and Jaguar. 'I wasn't interested in advertising Porsche,' he said, 'so I changed the name.' Accordingly he rearranged the original lettering to spell PESCO.

His PESCO became Kaiser's daily driver. 'I had the feeling of driving a very lively and agile automobile,' he said. 'I had to park it in the darkest back streets of Zürich, because otherwise there would be a huge crowd of people around it when I returned. They didn't know which end was the front and which the back.'

In the spring of 1949 Kaiser sent the car to Metsch, a friend in Frankental in Germany, to have its brakes converted from cable to hydraulic operation. In 1951, after Porsche set up in business in Stuttgart, he took the roadster to the works, where he thought that it might cause some excitement. Instead he was told that they had no interest in it. This 'failed design' was nothing to do with them, the Porsche people told him.

In 1951 Peter Kaiser sold the 356 to Zürich VW importer AMAG for 4,500 francs. At the time, said Kaiser, its seats were uncomfortable, body seams were opening up, the doors were dropping after the hinges went, the seating between the frame trusses was narrow, the engine was weakening and the springing was suffering. 'It was falling to bits,' he recalled.

Shortly thereafter Rosemarie Muff of Zurich acquired the Porsche for 10,000 francs. After she drove the car into the ground, swanning slowly about the streets of Zürich, Hermann Schulthess bought it for 3,000 francs, still in 1951. Now the first Porsche felt that it was finally in good hands. Zürich's Schulthess, a car hobbyist, restored the 356 completely.

On a trip over the Gotthard Pass the Porsche nearly collided with a goat. Avoiding it, Schulthess braked so severely that the Opel following him, occupied by six nuns from the Einsiedeln nunnery, ran into him and pushed the 356 into the car in front. Both ends were repaired in the bodywork department of AMAG in Zürich, which altered both front and rear to align them more with the design of current production Porsches.

In 1952 Hermann Schulthess took the car to the Porsche factory for the installation of larger hydraulic brakes and a 1500S engine. The only person in the works who expressed pleasure at this reunion with 'our first Porsche', as he called it, was business chief Leopold Prinzing. Otherwise no one took a particular interest in it.

With its strong engine and great brakes, thought Hermann Schulthess, his car was race-ready. But the only actual race that 356 Number One entered was the Swiss Mitholz-Kandersteg Hill Climb in 1953. Mark Engler from Ascona drove it to second place behind winner Hans Stanek in his Porsche-powered Glöckler special. That year the car also participated in several Swiss rallies.

The next owner was Zürich master baker Igoris. It was love at first sight when he saw the 356 being inspected at AMAG. Igoris exchanged his Porsche 356 1300 coupe for the car with Hermann Schulthess. Although he wanted to renege on the deal the next day because Number One didn't meet his expectations, Schulthess refused. From then on the car stood in the garage of Igoris and deteriorated.

The last private owner of Porsche No. 1 was Franz Blaser of Laachen on the Zürich Obersee. On one of his daily trips to Zürich the auto mechanic spotted the car sitting in the Igoris garage and bought it. Again the car was completely overhauled, restored and returned to the road.

In 1958, celebrating its first decade, the Porsche works decided to retrieve the first car bearing the company name. The intention was to set up an exhibit at the factory in which all previous Porsche designs would be assembled and admired. Porsche's Richard von Frankenberg, a friend of Hermann Schulthess, assumed that he was still in possession of No. 1 and asked if he would sell the car. Frankenberg was referred to Blaser, who happily exchanged his ten-year-old roadster against a factory-new Porsche Speedster.

Thereafter 356-001 has been in the Porsche collection. Around 1975 it was restored to an approximation of its original external appearance, though its interior had been much changed with a new dash and buckets instead of bench seating. Buffed and primped to a fare-thee-well, it is justifiably a prime attraction in the new Porsche Museum.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Porsche and the Vees

The symbiosis between Porsche and Volkswagen was exemplified by the Stuttgart company's role in the establishment of Formula Vee in Germany. Porsche's Austrian sister had an important role as well.

That failure is an orphan and success has many fathers is a well-known axiom. It was never truer than in the instance of Formula Vee's launch in Europe, in which Porsche played a major role. This racing class, based on the extensive use of near-standard VW drive train and suspension, had its origins in sunny Florida.

Another category served as the cradle for Formula Vee. In 1959 Formula Junior was all the rage, a class for single-seaters that used standard 1.1-litre engines but allowed more design freedom otherwise. Florida enthusiasts Hubert Brundage decided that this would suit VW's flat four so he commissioned Turin's Enrico Nardi to fashion a Formula Junior from Volkswagen raw material. As his Brumos was America's south-eastern distributor for Porsche and VW, this was right up Brundage's street.

The result didn't measure up to Brundage's hopes. The air-cooled VW couldn't cope with the Fiat fours that powered the early Juniors. However a retired Air Force colonel, George M. Smith, saw promise in the concept. His vision was of a one-make category for cars akin to sailing's Star boat class, which gained a reputation as the 'poor man's racing yacht'. A VW-based single-seater, Smith thought, could serve the same purpose in motor racing.

After competing with the Nardi-built car through 1961 Smith sparked the establishment of Florida's Formcar Constructors Inc. to produce such cars in series. By the end of that year several were racing. In 1963 more were campaigned, showing the merits of this simple but effective concept, and in 1964 the Sports Car Club of America ran the first Formula Vee National Championship. Rules were set that allowed any maker to produce Vees to a strict set of guidelines. By 1965 some 700 Formula Vee single-seaters were introducing Americans to the fun of open-wheeled racing.

In these natal years of Formula Vee, Carl Hahn headed Volkswagen of America. He witnessed with fascination the growth of this new class based on his Beetles. 'During an Easter holiday in the Bahamas,' said Hahn, 'my wife and I enthusiastically drove Vees…though not in races.'

Soon Hahn, a success in America, was recalled to Wolfsburg to take over sales for VW. 'Back in Germany,' he recalled, 'the idea soon arose to bring this popular form of motor sports from the USA to the European continent.' He approached his chief, Heinrich Nordhoff, with the idea. 'Nordhoff gave me his permission,' added Hahn, 'with a budget of DM100,000.

'With the help of Ferry Porsche and Porsche racing director Huschke von Hanstein, a good friend,' Carl Hahn continued, 'overnight the cost-effective Formula Vee racing car became numerically the world's biggest racing-car category. There were 2,500 of them. Volkswagen couldn't lose.'

Von Hanstein recollected the sequence of events differently. He was president of the ONS, Germany's highest motor-sports authority. In this post, he said, 'I was concerned because in Germany, unlike in neighbouring countries, very little was being done for future generations in motor sports. When I saw a small, affordable racing car at one of our American dealers I became quite excited by its prospects. It consisted of a race-car body sprung by VW suspension components.' This would have been during a visit to Brumos in the course of a March Porsche entry at Sebring.

In Huschke's telling of the story he returned to Stuttgart and 'attempted to convince Ferry Porsche to establish such a racing series in Germany. It would give a tremendous PR boost to motor sports and of course for Porsche. Ferry was sceptical at first, because the cars used VW components.'

In the von Hanstein version he then took his idea to Carl Hahn while the latter was still in his VW of America chair. Getting Hahn's assent to his scheme, Huschke arranged for the VW man to meet with himself and Ferry during his next trip to Germany. In that meeting, said Huschke, Ferry was won over and the European Vee project was approved. Any reservations that Ferry had were certainly eased by the application of Hahn's 100,000 deutschmarks, equivalent at the time to $25,000.

Early in 1965 Porsche imported ten kits, both Beach and Formcar designs, and installed VW power trains to launch this accessible form of racing in the Beetle's native land. Von Hanstein's modus operandi was to take the show on the road, putting on short demonstration races in key cities with invitations to local hot-shots to try these odd-looking racers. Then the first fleet was placed at the disposal of the big clubs, the AvD and ADAC, without charge to give 'Formel Vau' a running start. The first serious races, held that summer of 1965, had the desired effect.

'Our success surprised us,' admitted von Hanstein. 'We only wanted to see how much interest there was and whether companies could be found to build the cars. The matter took off on its own. In short order several clever young men had built their own tiny racers based on the American examples.'

With Huschke in charge at the ONS it took no time at all for 'Formel Vau' rules to be drawn up and approved. While American Vees had 1.2-litre engines, the European rules catered for the VW's 1.3-litre version since that was the more common capacity in the Old World. For the class's first two years in Germany it was supported at each event by two Porsche engineers. They checked the cars for safety and rules conformity before and after each race and provided technical advice.

'Anton Konrad, Volkswagen PR chief, was manager of this racing series,' Carl Hahn related. 'He found enthusiastic support from our main dealers and importers. This broke the ice. For the first time VW and motor sports found each other.' VW's direct support continued until 1976, after which it bowed out and left its development to private hands. Other categories had been added such as Super Vee, in 1971, to accommodate 1.6-litre engines and more sophisticated chassis designs.

At Leonberg, near Stuttgart, Fuchs produced a 'Formel Vau' that was exceptionally trim. Near Bonn another company got into the act with its Gepard Vee. Added to the ranks from early 1968 was McNamara Racing, at Lenggries at the foot of the Bavarian Alps.

Sounding anything but German, McNamara was established by an American Midwesterner who caught the racing bug while with the U. S. Army in Germany and decided to build cars of his own. 'We couldn't buy what we wanted,' said Francis McNamara, whose 'Sebring' Vees were highly successful. The goateed McNamara went on to produce cars for higher categories up to Formula 2 and, surprisingly, an Indianapolis racer designed by Jo Karasek, a former Porsche engineer.

Just as they had in Germany, the cheeky Vees sparked strong motor-sports participation in Austria by that nation's VW importer, Porsche Salzburg. There Ferry's sister Louise Piëch and her son Ernst Piëch took up the new category with verve. Austro and Bergmann produced Vees, among others making Austria a leading source of the new racers. At Salzburg Paul Schwanz specialised in engine preparation for the formula.

A key actor in both versions of the story of Formula Vee's launch in Europe, Porsche's Huschke von Hanstein could be proud of what he'd achieved. The cars, he enthused, were 'dirt cheap and you could take them to races on a lightweight trailer. Interested hobbyists could buy the appropriate parts directly from VW. Then it was only a question of their own skill and aesthetic sense for what body they dropped on the frame. Tyres, suspension, transmission and engine were identical for all competitors and easily checked by the organisers. In Formula Vee anybody who came out ahead of his competitors was truly a better driver because their equipment was identical.'

That Vees provided a suitable training ground for talent was verified by the results. Von Hanstein's aim of a step up the ladder for his home-based talent was achieved. From the Vee ranks came leading German drivers including Jochen Mass, Harald Ertl and Klaus Niedzwiedz. Austrian stars in the category were future world champions Jochen Rindt and Niki Lauda as well as Helmut Marko, today the eminence grise of Red Bull Racing. Champions Emerson Fittipaldi-who produced Vees in Brazil-and Nelson Piquet also cut their teeth driving these racers.

'For me the circle closed in 1990,' said Carl Hahn, without whose support and subsidy the European breakthrough might never have happened. 'That's when we honoured Michael Schumacher for his Golf-powered German championship in Formula 3.' With a little help from Porsche, Volkswagen had indeed broken the ice to go on to success in motor sports. The Vee also sparked the competition activity of Porsche Salzburg, whose backing of major endurance-racing entries was key to the success of the immortal 917.

- Karl Ludvigsen

How a Tail-Dragger Saved the 911

An analogy with aviation helped a new Porsche chef executive restore confidence in the company's 911 at a crucial stage of its evolution.

When I first drove a Porsche 928 on 26 February 1977 I was eager to get a sense of its road manners. After their years of massaging the handling of the rear-engined 911, how had Porsche's engineers managed the transition to a powerful front-engined sports car? My impressions were interesting.

'The steering is not so precise and direct as a 911's - what car's is? - but it is almost that good,' I wrote at the time. 'Only a slight numbness hints at its power assist. It controls road handling that's the definition of neutral. It's so predictable that you simply track it through turns faster and faster until, near the limit, the front tires shudder a warning and the rear rubber gently, controllably slackens its grip on the road.'

My colleague Tony Curtis of Motor seemed to agree. He wrote that the 928 'handles magnificently,' adding, 'There is a sense, indeed, in which the 928 has no handling at all: it simply goes round corners where the driver wants it to go without effort or fuss.'

This had all the hallmarks of high praise from both Tony and myself. What could be better than balanced, neutral handling? The self-adjusting 'Weissach' rear suspension was doing its job, also helping to make the 928 Europe's Car of the Year.

In 1981 Germany's auto motor und sport compared the then-new 928S with a 911 Turbo. On curving country roads it found the Turbo's 'hectic' throttle response less satisfying than the 'beautiful balance' of the V-8's power production. After five hours on the Autobahn, said ams, the 911 Turbo driver 'is visibly bushed and figuratively gives himself a pat on the back. The 928S pilot steps out his capsule relaxed and without bands of perspiration under his armpits. There's no doubt about it: almost immune to the effects of side winds and responding stoically even in 125-mph curves, the unerringly straight-rolling 928S is here the car nearer perfection.'

But...was perfection really what people wanted from a Porsche? Had this striving for immaculate handling led to a more banal, even boring, driving sensation? Some light on this relationship between the 911 and the 928 is shed by remarks that former Porsche chief Peter Schutz contributed to a new book I've written for Bentley Publications, Porsche - Origin of the Species, to be out later this year. Schutz, who was CEO at Zuffenhausen from 1981 through 1987, set the scene as follows:

'In the mid-1960s Porsche introduced its 911 as a successor to the 356. Confirming the direction established with the 356, the 911 extended the growth of a successful Porsche automobile business. Its unique rear-mounted air-cooled engine made unusual noises that were theme music for true Porsche lovers. Light and powerful, the 911 had unique handling characteristics. In the hands of a capable driver it was extremely quick.

'But the 911 wasn't easy to drive, It had a tendency to spin in a fast curve if mishandled. The 911 had its origins in the Volkswagen Beetle. Although highly evolved from that machine, the 911 retained some of the cantankerous handling characteristics of its ancestor.

'In the early 1970s the Porsche and Piëch families withdrew from active management of their company. The first head of Porsche who was not a family member was Ernst Fuhrmann, a brilliant engineer. During his tenure Fuhrmann undertook the task of replacing the Porsche 911 with two water-cooled front-engined cars, the Porsche 924 and 928.

'A great deal of sound technical thinking went into these new Porsche models. One objective was to eliminate the perceived instability or nervousness of the rear-engined 911. This characteristic, its directional instability, can be described in positive terms as manoeuvrability.

'It depends on the driver's point of view. Some drivers love a car that is stable, that continues to go straight until the driver acts to make it turn. It goes in the direction in which it is steered. On the other hand some drivers love a car that will change its heading as a function of actions other than just steering. Highly manoeuvrable racing and sports cars can be steered with the throttle and brakes in fast turns.

'The new Porsche era was to be built around the 924 and 928 models powered by liquid-cooled front-mounted engines. Their layout eliminated the cranky characteristic of the rear-engined 911, the tendency for its rear to be chasing its front if its driver released the gas pedal too suddenly in a fast turn.

'As well, prevailing opinion at Porsche was that the rear-mounted air-cooled engine couldn't be brought into compliance with anticipated noise and exhaust emission legislation. A decision had been made to move Porsche beyond the air-cooled, rear-mounted-engine era. Accordingly the Porsche 911 was scheduled to be discontinued at the end of the 1982 model year.

'Such was the posture of Porsche in the spring of 1980 when the Porsche family decided to replace Ernst Fuhrmann as CEO of Porsche A.G. On January 7, 1981 Sheila and I went to Stuttgart as husband and wife and became a part of the Porsche team. It was time to get down to business and begin the task of rebuilding Porsche.

'In many discussions with Porsche employees, owners and customers I had learned enough to have an inkling of what was wrong. Whenever I talked with Porsche enthusiasts, the conversation eventually came back around to one subject that seemed to be on everyone's minds. The company's two major challenges, the lack of profitability and the poor morale, appeared to have their foundation in the same development: the planned discontinuation of the still-popular Porsche 911 sports car.

'The 911 was challenged on numerous occasions. Many wondered why Porsche persisted in propagating its strange handling characteristics when state-of-the-art engineering could facilitate far more civilised performance. The Porsche Australian importer visited me in my Stuttgart office and put the question to me: "Why does Porsche continue to build such a difficult-handling car, a car that requires a driver with above-average skill to drive well?"

'I derived my answer from my flying experience. I had been a pilot for several decades. Most of the aircraft I'd flown and owned over the years had tail-wheel landing gear instead of the more modern tricycle landing gear. A tail-wheel airplane has more treacherous ground-handling characteristics than its tricycle-gear counterpart. A tail-wheel airplane will ground-loop, careen in a sharp circle and, in some instances, end up on its back if not handled with skill and respect.

'One such airplane I flew for a number of years was a Fairchild PT-23, a World War II Army Air Corps training plane. I explained to my Australian visitor that when I flew this airplane to a small airport and did a chandelle after a high-speed pass over the runway, followed by a perfect wheel landing, every eye on the airfield would be waiting to see who got out of the airplane. They knew it took a bit more than average flying skill to carry that series of manoeuvres off well. It was a point of piloting pride.

'In like manner, when a Porsche 911 owner drove their car well it garnered the respect of peers, a point of driving pride. The point had been made. A few weeks later I received a gift from several Porsche importers: an aircraft tail-wheel mounted on a beautiful wood plaque with the inscription: "To the Porsche tail-wheel philosophy."

'A deep sense of loss, a grieving that was almost heartbreaking, was gathering like a storm. Elegantly engineered though they were, the 924, its successor the 944 and the 928 weren't real Porsches in the eyes of the hard-core Porsche faithful. None of these new vehicles was able to replace the about-to-be-discontinued Porsche 911 in the hearts of Porsche customers and dealers. To me, a newcomer, the feeling of impending catastrophe was overpowering. It was essential for us to recognise what our faithful hard-core customers were looking for and make sure we gave it to them.

'The decision to keep the 911 in the product line came one afternoon in the office of Helmut Bott, the Porsche operating board member responsible for engineering and development. I noticed a chart on Bott's office wall. It depicted the development schedules for the three primary Porsche product lines: 944, 928 and 911. Two of them stretched far into the future, but the 911 programme stopped at the end of 1981.

'I remember rising from my chair, walking over to the chart, taking a black marker pen and extending the 911 programme's bar clean off the end of the chart. I am sure I heard a silent cheer from Helmuth Bott. In his calm, reserved way he emitted a loud hurrah! I knew we had done the right thing. The Porsche 911, the company icon, had been saved. I believe the company was saved with it.'

In the future the 911 would face several more challenges. This, however, was one of the toughest. Thanks to an apt analogy with tail-wheeled airplanes, it survived to fight another day.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Those Pesky Porsche-Abarths

Among the many riddles the author had to solve in the updating of Excellence was the identity of the makers of the Porsche-Abarth bodies. This led him a very merry chase.

In 1960, when the Abarth-bodied Porsche Carrera came to life, I was the editor of Car and Driver at Number One Park Avenue, New York. I received a brief report and photos of the new model from my friend and colleague Edward Eves. We printed verbatim his information that the bodies were being made to Abarth's design by Milan coachbuilder Zagato. When I wrote my history of Porsche I said the same thing. This got me in a lot of trouble.

As researchers dug into the story of these cars, the Zagato attribution looked more and more fragile. For example Zagato denied having anything to do with them - kind of a clue there. Other coachbuilders started to be mentioned. It looked like I had some work to do for the updated version of Excellence.

It's time for a bit of back story. The motivation for improving the Carrera wasn't to improve its racing performance in the 1,600 cc GT class. The MG Twin-Cam had proved less than a menace. But competition between Lotus Elites and Alfa Romeo Giuliettas in the 1,300 cc GT class was so intense that they were gaining on the Carrera's lap times. To avoid the embarrassment of being overtaken by these small fry, Porsche moved to improve its Carrera for 1960.

The FIA's GT-class rules allowed a different body, as long as the car's weight remained above the homologated figure - an invitingly low 1,712 pounds. In the summer of 1959 Porsche asked two suppliers for bids on the manufacture of 20 special lightweight bodies for the 356B chassis: Wendler, the nearby maker of Spyder bodies, and our prime suspect Zagato.

As so often happens in Italy, news of a new project spread quickly. During the rest of 1959 past and present friends of Porsche got in touch to inquire about this body-building opportuny. Among them was Karl "Carlo" Abarth. In 1958 and '59 Abarth and his aide Renzo Avidano were successfully building and selling small-displacement Fiat-based rear-engine sports-racers that were, indeed, bodied by Milan's Zagato. Dirk-Michael Conradt's research tells us that Abarth journeyed to Frankfurt for its Auto Show in September, 1959. At the Frankfurter Hof he met on the 18th with the top men of Porsche: Ferry Porsche, sales chief Walter Schmidt and technical boss Klaus von Rücker.

For one million lire each, said Abarth, he would body 20 Carreras - this price to include his tooling. The bodies were to be 'as light as possible'. The cautious Ferry agreed in principle but asked that Abarth start by building one such body as a sample. October 21st was set as a deadline for Abarth to inform Porsche about the kind of body he would build and for Schmidt's department to confirm its sales objective and likely pricing.

Porsche named the experienced Franz Xaver Reimspiess as its liaison man for the project. He travelled to Turin to meet with Abarth on October 6th and 7th to go over project details. Reimspiess set out Porsche's requirements for the design, such as oil-tank location and engine-bay ventilation. Carlo Abarth engaged respected designer Franco Scaglione to prepare some proposed designs for the body.

Scaglione was a well-known stylist-engineer of sports-car bodies who had shown a special knack for aerodynamics. Reimspiess saw his first efforts during his visit. Reported the Porsche engineer, 'He will have the bodies made at ZAGATO, where of course he will closely observe the execution of the work.' Abarth also raised the idea that after this series was built for Porsche he might carry on the building and selling of such cars on his own account.

Franco Scaglione and Abarth were successful in achieving one of their main goals: a sharp reduction in the Porsche Carrera's frontal area. They slashed 5.2 inches from its height, reducing it to 47.2 inches, and cut the width down by 4.7 inches to 61.0. This had the effect of reducing the frontal area by about 15 percent. Scaglione's shape was also successful in the drag department, having a Cd of 0.365 with the engine-cooling flap closed and 0.376 with it open, usefully below the standard 356B body with its coefficient of 0.398.

The Carrera's Italian cure achieved a reasonable if not striking weight loss. Its body was made entirely of aluminium. Its structure was beefed up in order to increase the overall strength of the chassis, yet the first car weighed only about 1,760 pounds. This made it some 100 pounds lighter than the Reutter GT and a safe 50 pounds heavier than the homologated minimum allowed for its class.

But who was actually making the bodies? This was a turbulent period for Abarth, who in fact was just then severing his relationships with Milan's Zagato and sourcing his bodies from small and less-experienced Turin-based companies. Instead of Zagato, as planned, he changed to such a company to make the Porsche prototype. Thus instead of October 1959, as promised, the first Carrera GTL - as the new car was named - arrived in Zuffenhausen at the end of February 1960.

Historian Peter Vack attributes the first body, and perhaps more than one, to coachbuilder Viarenzo & Filliponi. Abarth wasn't eager to disclose that he had changed body sources. When the car was first revealed at Abarth's factory in Italy, Ted Eves was told that Zagato was its coachbuilder. However Zagato confirmed to researcher Donald Peter Cain that it had not, after all, been involved in the Carrera GTL project. Abarth may not have wanted Porsche to know that he was using a different - and doubtless cheaper - source for his bodies. Such a revelation could have led to a downward readjustment of the price he was being paid for the work.

Late-winter rain found the first car leaking profusely on delivery. There was next to no headroom, even for the shorter Porsche men. This was remedied by relocation of the seat tracks and changes in the seat cushioning and the back angle to add several inches of headroom. Porsche also found that the front-wheel openings had been trimmed so tightly that steering lock was limited, especially when a wheel moved upward on jounce. In spite of the instructions given by Reimspiess the mounting of the oil tank was unsatisfactory, its cooling inadequate.

With problems like these resolved, the run of production cars was bodied for Abarth by the Turin workshop of Rocco Motto. Motto's flexible facility was staffed by '45 men and three power hammers,' as he put it, proudly including the hammers among the staff. Motto was well prepared for the visit by Carlo Abarth who, he said, 'was a rough diamond and was always shouting. I told him "no". He made me change my opinion; now he seemed like a well-mannered friend. Such times!'

Motto's work made a positive impression on the engineers from Zuffenhausen. 'The German engineers were full of enthusiasm and suggested that I should go to Germany,' said the coachbuilder. 'They were prepared to create a section just for me. If they had proposed that I would be able to lord it over them there, I would have gone. But just to work, Turin was better.'

During 1960, starting with Strähle, private owners took delivery of their GTLs. The final serial number was 1021, bringing to 21 the population of Abarth-Porsches. Cars 1013 and 1018 were kept by the factory for works entries. Both they and the privately entered GTLs racked up outstanding racing records well into 1963.

In September of 1962, at Monza for the Italian Grand Prix, Huschke von Hanstein huddled with none other than Carlo Abarth to discuss a brainwave. Huschke said that he was thinking of taking the bodies off his 1.6-litre Carreras and putting them on the new Carrera 2 chassis. 'To be sure he did not find this solution very elegant,' Huschke reported Abarth's reaction.

Abarth told the Porsche racing chief that he'd be glad to build new bodies to the same pattern for Porsche. He would require, however, an order for at least 25 bodies to make the project economical, even if he didn't expect to make much money, he told Huschke: 'By mentioning his name the Porsche-Carrera-Abarths have brought him so much world-wide publicity that he has no need whatsoever to make a profit' on the new Porsche job.

This contact was followed up in October by Porsche with the view of having the 25 bodies completed by 25 June 1963, the latest date at which they felt they could be assured of selling the cars. By the end of 1962, however, the idea was dropped. Instead, craftsmen back home at Porsche were assigned the job of making a new light body for the Carrera 2. Its shape would be the responsibility of Ferdinand 'Butzi' Porsche, opening a new era in styling at Zuffenhausen.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Porsche's F.1 Formulae

In various roles as designer, builder and racer Porsche has been involved in Grand Prix racing since 1922. What does this tell us about the modern company's role if and when it returns to this demanding sport?

When new Porsche chief Matthias Müller hinted that Formula 1 could be on the VW Group's agenda and might even fall to Porsche to implement, he caused big ructions in the tight little world of the Stuttgart sports-car maker. His remarks at the Paris Salon were to the effect that VW would have an internal round-table discussion late in 2010 to sort out the respective racing ambitions of Audi and Porsche. One of them, he mooted, could be competing in Grands Prix.

G.P. racing is in Porsche's blood. Ferdinand Porsche designed a Grand Prix car for Austro Daimler in 1922, the ADS II-R, and a Mercedes G.P. entry when he worked for Daimler in 1924. When he departed in 1928 he left behind a design that set the pattern for the 1934 Grand Prix Mercedes-Benz. Among the first projects by Porsche's own design office was the Type 22, the G.P. car built and raced by Auto Union from 1934 through 1937.

From 1937 through 1939 the Porsche office was a consultant to Daimler-Benz on its G.P. car designs. Its Project 108 was a two-stage supercharger that led to the use of that principle on the 1939 racing Mercedes-Benz. Type 116 was a 1½-litre racing-car study under a Volkswagen contract, based on the Type 114 F-Wagen sports car. And of course in 1947 Porsche designed its mid-engined Type 360 for Cisitalia, the supercharged 1½-litre flat-12 that was one of the most advanced conceptions of a racing car for its era.

All these designs were prepared by Porsche. In some cases the company also participated in the development of the racing cars it created. As well, with his designs for Austro Daimler in 1922 and Mercedes in 1924 Ferdinand Porsche had full responsibility for the construction, testing and actual racing of his cars.

When the Porsche company finally made a wholehearted commitment to Formula 1 it sleep-walked into the category, drifting into it in stages that seemed both gradual and easy. As Ferry Porsche said, 'At first we ran in Formula 2 with modified sports cars and won some races. Since we won in Formula 2 easily we thought, "Why not go into Formula 1?"'

By adapting the RSK's suspension to a new narrow frame Porsche built its first open-wheeled single-seater in 1959 to compete in the 1½-litre Formula 2, powered by the Fuhrmann-designed four-cam Spyder four. This soon showed sufficient form for the Rob Walker stable to run one in 1960 for Stirling Moss, who enjoyed some Formula 2 success. Thus it was a no-brainer for Porsche to commit to the new 1½-litre Formula 1 of 1961 with the strong driver team of Jo Bonnier and Dan Gurney.

One of the big attractions of Porsche for Dan was the knowledge, imparted by racing chief Huschke von Hanstein, that the company was developing an all-new flat-eight 1½-litre engine. The Porsche men had sensed that the demands of the new Formula would exceed the ability of their trusty Fuhrmann-designed four. Work therefore began at the end of 1959 on an engine that would be intrinsically capable of producing more power. Secondary, at that time, was the question of what kind of car would use it.

Early in 1961 Porsche released photos of its new Grand Prix eight but no details about its design. As the editor of Car and Driver I was naturally extremely curious about the innards of this all-new engine. External views betrayed little of such vital features as camshaft drive and valve gear.

When in August of 1961 Mercedes-Benz organised a press junket to Austria and Germany, I made a side trip to Porsche. Huschke von Hanstein took me into the sanctum sanctorum where the F.1 engines were being torn down and rebuilt. I eyeballed them in depth and detail.

In the January 1962 issue of Car and Driver I reviewed the new eights being prepared for Formula 1, the Porsche included. Helped by information from Swiss engineer Michael May, a Porsche insider, I described the struggles with the new unit, including its disappointing 120 horsepower when first run. In fact, I wrote, 'Porsche opinion in mid-1961 was veering toward a decision to toss the engine out and start from scratch again.'

Accompanying my story was an illustration by my friend Tom Fornander that showed the engine's cam-drive train, based on my description after Huschke's private preview. It was an elaborate affair with the crankshaft between upper and lower half-speed shafts, from which other bevels and shafts drove the cams at their centres. More shafts drove the distributors for dual ignition and an axial-flow cooling fan.

Alert editors at Germany's auto motor und sport picked up this drawing and published it together with some of my comments about the engine. They'd been denied any glimpse of its innards so this was big news for them and their readers. The upshot was embarrassment for Huschke von Hanstein, who wrote to me in self-justifying terms clearly intended to divert blame for this indiscretion away from himself in the eyes of his superiors. I'm happy to say that we remained friends in spite of one of my better mini-scoops.

The record shows that in 1962, the only season in which Porsche competed with a car built especially for Formula 1, it entered seven out of nine World Championship events. It won one and placed third, fifth, sixth, seventh and ninth in five others. The single Championship Grand Prix win was scored by Dan Gurney in the French G.P. at Rouen on 8 July. Porsche placed first and third in the two non-championship races it entered. Its drivers were ranked fifth (Gurney) and 15th (Bonnier) in World Championship standings. Its car stood equal fifth with Ferrari among the seven marques that won points in the Formula 1 constructors' challenge in 1962.

This couldn't be called a litany of disaster. Only once, when a lone car was knocked out by another on the first lap, did a G.P. Porsche fail to finish a race that the team started. This was one of only four retirements among 13 eight-cylinder entries in championship G.P. races. The others were the fault of the drive train: the ring and pinion gears twice and the shift linkage once. Not once in 1962 did engine trouble knock a Porsche out of a Grand Prix race.

Porsche took for granted in 1961-62 that it would build the entirety of its Grand Prix cars. It had the technology to do so with its hard-won knowledge of suspensions, structures and materials. A handicap was its lack of access to a German network of small, specialised suppliers like the ones that underpinned the efforts of its British rivals. Though excellent, Porsche's domestic suppliers had little appreciation of the urgency that racing demands.

Porsche's subsequent Formula 1 entries have been as an engine supplier. The twin-turbo V6 that it created for McLaren under contract to TAG Turbo Engines was a storied success, winning the drivers' title for Niki Lauda in 1984 and successive crowns for Alain Prost in 1985 and 1986. The V12 that it supplied to Arrows in 1991 was, in contrast, a flop, while the V10 that Porsche designed to replace it never had a chance to show what it could do.

Significantly, the Type 2708 single-seater that Porsche entered in the CART series in 1987-88 was entirely an in-house effort, both engine and chassis. Its early struggles in the American series were attributed to chassis faults rather than lack of power, though the latter was ultimately found to be the more significant deficit. When a hasty switch was made to March chassis, the Weissach engineers lost interest. 'The light went out' as one of them said. The programme never recovered.

There's a lesson here for today's Porsche management. Though an entry into Formula 1 as an engine supplier might seem a low-risk approach, seeking to emulate the glories of the mid-1980s, it's half-hearted in today's Grand Prix racing where Ferrari and Mercedes-Benz have their own integrated car-building teams. Just making engines would be demotivating to a technical team that has mastered whole-car racing challenges with great success, most recently with the brilliant RS Spyder in the ALMS and at Le Mans.

There's no escaping it: any Porsche Formula 1 entry has to be a complete automobile. No other approach to the series would suit the Porsche reputation for outstanding engineering of all aspects of a vehicle. More problematic is the issue of how the cars would be entered and raced. Would Formula 1's rules allow the involvement of a private team like Roger Penske's with the RS Spyder or Reinhold Joest's with Audi? Sorting this should not be beyond the wit of men as resourceful as those at Porsche.

- Karl Ludvigsen

The Auto Union Connection

When Ferdinand Porsche set up his own engineering company in 1930 he urgently needed customers. First Wanderer and then Auto Union came to his rescue, making 'Auto Union' an apt name for the future company combining VW and Porsche.

It all started with Wanderer. Though an automaker since 1896, Siegmar's Wanderer struggled to find a formula for success during the 1920s. From September 1928 a new head of sales, Baron Klaus Detlof von Oertzen, enlivened its marketing, recruiting famed racing driver Rudy Caracciola to front a new dealership on Berlin's proud Kurfürstendamm.

Klaus von Oertzen was a keen motor-sportsman, so much so that he went all the way to Sicily for the 1924 Targa Florio where he wangled his way onto the Mercedes team, for whom he acted as timekeeper. Mercedes won the great classic race with a car designed by Porsche, who invited von Oertzen to the victory dinner in Palermo. This was an important contact for the young Baron.

By 1930 Wanderer was feeling the Great Depression's pinch. Sales of 2,719 cars in 1929 were heading toward 1,319 in 1930. The company needed an injection of up-to-date engineering. Klaus von Oertzen told his board that he had just the man. "He wanted to do something and was pleased to get contracts," von Oertzen said of Ferdinand Porsche, who was establishing his own engineering company in Stuttgart in 1930. He urgently needed customers who would exploit the skills of his small but expert team.

They agreed on three projects which were sanctioned on 29 November 1930, five months before the new Porsche company was officially registered. The Type 7 was to be a six-cylinder 1.5-litre car, the Type 8 a 3.5-litre eight and Type 9 a supercharged version of the eight. Famously the Porsche men gave the number 7 to their first project to avoid giving the impression that they were starting from scratch-which of course they were.

The Type 7 emerged as a six-cylinder produced at the sizes 1,692 cc and 1,963 cc, achieved with differing-diameter wet liners and pistons in an aluminium block along the lines that Porsche had proven at Steyr, with pushrod-operated overhead valves. The new engines were installed in existing Wanderer models from October 1932 and at the Berlin Show in March 1933 were equipped with Porsche's completely new underpinnings including rear swing axles.

As part of this revival Wanderer's conservative chief Hermann Klee was persuaded to think of building a racing car to raise his products' profile. The persuader of course was Klaus von Oertzen, who arranged for Klee and Porsche to discuss such an effort more concretely at the 1931 Paris Salon.

In October of 1932 the rules were announced for the Grand Prix formula to take effect in 1934; they limited car weight less tyres and liquids to 750 kilograms, 1,654 pounds. Two weeks later, on 1 November 1932, Porsche and his team drew up preliminary specifications for their Type 22: a mid-mounted V16 engine of 4,358 cc and an operational speed of 4,500 rpm.

Meanwhile, under the patronage and with the encouragement of the state of Saxony, in 1932 four of its depression-hit car and motorcycle makers, Wanderer, Horch, DKW and Audi, pooled their assets in a single organisation, the Auto Union AG. Baron Klaus Detlof von Oertzen became a deputy management-board member. All valid contracts of the member companies were carried over, including those of Porsche, who was working not only for Wanderer but also for Horch.

The creation of Auto Union opened an opportunity for Porsche's racing car. A new automotive combine needed powerful publicity. The new company's top executives, Richard Bruhn and William Werner, were ambivalent about the value of racing. Was it more than a frivolous diversion from the tough job of making and selling cars in a depression? They already had confidential confirmation of the plans of Daimler Benz to re-enter racing; they felt they might have to compete with the Swabian firm on the track to support the sales of their costly and luxurious Horch.

In January of 1933 Klaus von Oertzen presented the Type 22's case to the Auto Union management board. Very well, the directors responded, it sounds promising, but where are we to get the money to do this? They would get encouragement from an unexpected source. It had been no secret that Adolf Hitler, leader of Germany's National Socialists, was keen on cars. His party had steadily been gaining support.

On Monday, 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was named Germany's chancellor. Only a few days later in his speech at the opening of the Auto Show in Berlin on a Saturday, 11 February, "he set out the guidelines of a mass mobilisation of Germany: tax abatements for car buyers, the building of the Autobahns, repeal of obligatory driving school and encouragement of motor sport."

Soon Daimler-Benz negotiated a commitment by the new Third Reich to provide a subsidy for the cars it was building for the 1934 formula. As by far the nation's leading producer of racing cars the Mercedes-Benz maker was confident that it had a monopoly on this important mission. Directed by his board to get support from the Third Reich, Klaus von Oertzen had his work cut out.

Von Oertzen prepared his arguments well, but no one would let him see Hitler, who was immensely busy with the tasks of the first weeks of his administration. "Then I went to see his deputy, Rudolf Hess," von Oertzen related. "He and I were pilots of yore; we knew each other from the Great War. I asked Hess to get us an appointment with Hitler. Hess then arranged it for the beginning of March."

The Baron laid his plans carefully. The appointment was set for Wednesday, 1 March 1933. At a meeting on the preceding Monday, Porsche and Auto Union reached agreement in principle on the outlines of the racing-car project. Von Oertzen: "To this meeting [with Hitler] I took Dr. Porsche and the racing driver Hans Stuck, who unlike myself was personally acquainted with Hitler."

At the old Chancellery in Berlin, shaped like a horseshoe with its open court facing the Wilhelmstrasse, the trio were given a sombre reception by the Führer. To von Oertzen's opening overtures Hitler gave not a hint of acquiescence. The Baron persisted, saying he owed it to Auto Union's ten thousand employees to press his case for support. Turning away from the emissary, Hitler addressed Porsche, who opened his portfolio on the glossy surface of the massive conference table.